Hudinilson Jr. | Fazer Tricô

An exhibition of work by Hudinilson Jr. curated by Manuel Segade

*In the jargon of São Paulo’s homosexual subculture, Fazer Tricô is a long conversation amongst homosexuals, mostly gossip on activities within their own minority culture. It literally means ‘to knit’. In the context of Hudinilson Jr.’s exhibition, it refers to the possibility of adopting a stance through writing that allows for the unravelling of a specific language’s inflections, corresponding with the framework of a marginal social field such as that of homosexuals in 1980s Brazil, yet aimed at a broader audience.

Hudinilson Urbano Junior (São Paulo, 1957- São Paulo, 28th of August of 2013) studied Fine Art at the Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation in the mid 70s, and began to experiment with drawing, painting, graffiti, mail art, performance, and urban intervention. His first big moment of public visibility came up in 1979 when he founded the collective 3 Nós 3, together with artists Màrio Ramiro (1957) and Rafael França (1957-1991). From its foundation and up until its dissolution in 1982, the group carried out public actions that saw the city as a page on which to compose graphic design, thus inserting monumental gestures in the city of São Paulo during the military dictatorship.

From then on, Hudinilson Jr. began his most mature individual work in an unusual context: after decades of a repressive regime in Brazil, a political relaxation began to emerge, announcing the arrival of democracy. While the actions of 3 Nós 3, including the photo novel CASOS – produced in 1978 and reprinted in 2014 on occasion of the tribute exhibition to Rafael França at the Jacqueline Martins Gallery in São Paulo-, were defying the established social and urban order, Hudinilson Jr. was questioning the dictatorship’s scopic regimes through his first Xerox works. The precise and categorical control of citizens’ bodies in a military regime was substituted in his oeuvre by the opacity of his own flesh, by the metonymical promiscuity of the relations between the different parts of a social self-portrait.

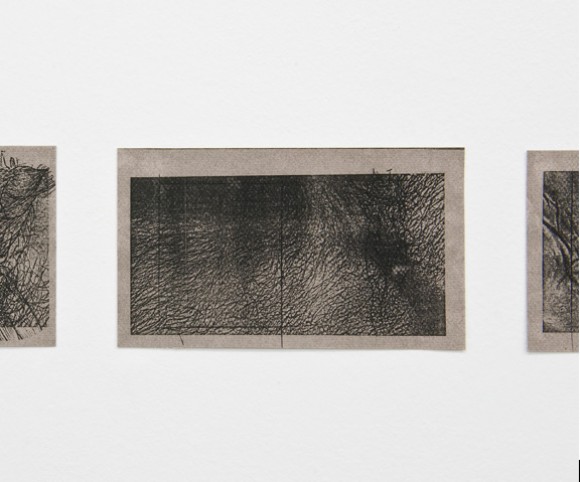

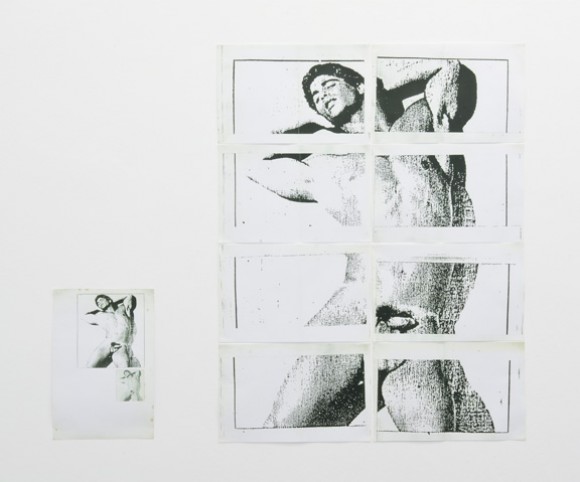

Exercícios de me ver of (“Exercises for Seeing Myself “), from 1982, turned Hudinilson Jr. into a pioneer of Xerox art in Brazil. The images document a singular type of performance literally showing him in the act of having sex with a photocopying machine, without looking at the camera, without any possible interaction with the audience, in the narcissistic exercise of fucking himself in order to obtain the fragmentation of his own image on a 1:1 scale. The works on paper resulting from the interaction between the artist’s body and the photocopying machine maintain a militant homoeroticism: they must be understood in relation to the sexual liberation taking place just before the AIDS crisis, which in Brazil coincided with the advent of democracy, a civil government having been established in 1985.

The photocopied images of the artist’s body lie halfway between traditional drawing and abstraction thanks to the graphic images of matted hair on the machine’s glass plate, but they also include other references: the aesthetics of fragmentation refers to culturally established notions of the body such as diagrams or measurements of it following the modern architectural canon, incorporated here as transparencies over the image. The cultural reference refers to the continuous movement, through the work’s public exhibition, between one’s own body and its social meanings, legible to the group in their daily environment: a sort of symbolic promiscuity where voyeurism is seen as a desiring machine that dismantles the political system. The interaction of the nude body with the Xerox machine, on the other hand, subverts the logic of labour at the office, making the machine erotic and the bureaucracy fuckable, auratically allowing the object to return the gaze as a work of art. In this sense, the resulting photocopy is a shock: it sums up a series of performative actions and complex relations in a single final image that is the result of a broader and more complex process of biomechanical interaction.

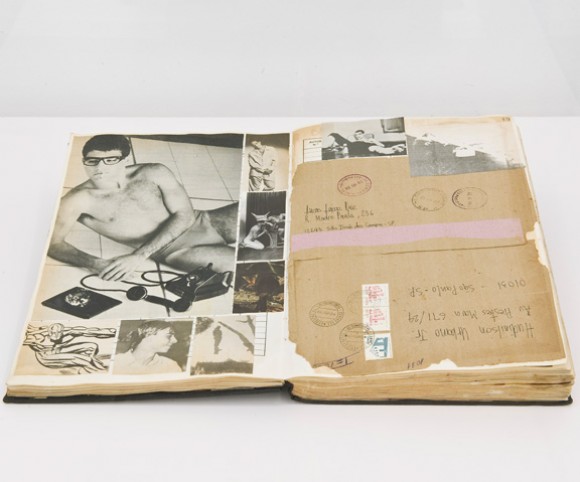

Whilst in these works and with 3 Nós 3 Hudinilson Jr. had advocated for a politics of symbolic contamination through gesture and his own body, these works in particular prepared him to face and resist the ostracism of contagion. Facing the at-risk-group with which the medical and legal apparatus identified homosexuals during the AIDS crisis, the collages he began working on at that time, which he continued to create up until the early 90s, refer to a support group; an affective and emotional closeness built through desire. The collages have not been shown often due to their pornographic character: all sorts of images from multiple sources proliferate on both sides of the cardboard base, like innumerable repetitions and anaphors, playing with semantic or formal analogy and continuous subtexts that rejoice in interrelations for the pleasure of an ongoing exegesis that fills the pages to the point of exhaustion. The philosopher Didier Eribon wrote that gays learn how to speak twice : once with the language inherited from the tradition they are inserted into, and secondly, from the non-hegemonic position he adopts as a life option. Which is why the ‘meta’ is part of his linguistic relationship with the world: a mutating and contextual relation, more pathetic than ethical, that is in continuous movement, whose meanings are not fixed, but produced through constellations where each and every one of its parts contaminates the next. Fragments of erotic magazines, popular iconography, advertising, record covers, and documentary photographs of the animal world make up a sort of Warburgian atlas of homosexual taste through a double movement: a picture of homosexual symbolic communication that combines global symbols with those from its own visual jargon.

Through their closeness to homosexual desire’s repetitive pornographic signs, the widespread circulation of the natural world and of popular culture thus creates new forms of nature and new contextualised references for this subculture. At the same time, the visuals of gay pornography, together with popular culture from the 80s and 90s, bring together gay sex and the photogenic qualities of natural history to question the heterosexuality of the conventional gaze on history, culture, and nature as seen through printed media. Just as the sociologists Green and Trinidade indicate, ” due to the barriers and sanctions they are subjected to by global society, individuals immersed in group culture from marginal groups tend to develop a symbolic system that, on the one hand, facilitates communication amongst the individuals of the group, and, on the other, hinders understanding by those who do not participate of the same culture” .

If, as Barthes wrote, the speakers of a gendered language are forced to adjust their symbolic representations to pre-established grammatical structures, it is in artist books -of which Hudinilson Jr. kept over one hundred in his library- that the most extreme rebellion against hegemonic heterosexual visual culture’s grammatical structure is produced. As unique works, they cover the pages of the artist’s diary, exercise books, notebooks from catechism, or account books, to cross-dress them by filling them up with photographic clippings, press articles, tobacco wrappings, photocopies, personal documents… A constellation that combines the artist’s life -his everyday life-, with the encyclopaedic nature of collage in order to create a different form of self-portraiture, of the exercise of seeing oneself. The diaries work like anchors of traditions within everyday contexts. Hudinilson Jr. reorganises mass media’s reified messages into new ones that are constituent of difference. The iconographies generated for the gay or cult film market are like fixed proverbs, paintings of a community’s social memory. But this memory is a constituent form of subjectivity.

Since the 50s -with characters such as Darcy Penteado or Paulo Becker-, in São Paulo there has been a symbiotic relationship between artistic and intellectual life and the world of homosexuals. During the following decades, the city’s homosexual cartography was built more as a moral region than a ghetto. Hudinilson Jr.’s work of the past decades is a way of communicating the anonymous knowledge at the social core of a marginal minority and its affective networks. Hence the narcissistic introjection, and its search for a response. In a study about homosexuality that was groundbreaking for Brazilian sociology, José Fabio Barbosa explained that “in general, the feeling of love is an arrangement of attitudes and values associated with a fundamental desire for a response” .

Néstor Perlongher, another Brazilian sociologist, spoke in the 80s about the gay imaginary of São Paulo in terms of a baroque machine: there were numerous terms to describe a single subject, and a broad range of postures in the relational networks of masculine homosexuality . The network of cataloguing devices and changing taxonomies inscribed themselves on bodies like an energetic device, a symbolic hyper production “driving molecular mobilisations on the plane of bodily sensations.” In Guattari and Rolnik’s terms, Perlongher wrote: “In marginal trajectories, in nomadic or vagabond existence, in the sinister machinations of desire, in the shadowy corners, there is no inversion of established, normal, conventional roles taking place, but an affirmation – connected as it may be in many ways to molar, macroscopic, institutional logic- of an intense difference, of a different desiring logic” .

In these works by Hudinilson Jr., from photocopies that can be reproduced to infinity, to the superimposition of proliferating codes through collage, or the porosity between the intimate and the public in the diaries, there lies a constituent precarity: that of opposing jargons whose interstitial speech covers the frameworks of marginal urban discourse. His works draw up a landscape of subjective dissidence, where the reverberation of bodies and desires in the open field of his texts, for all his possible audiences, has not yet taken place.

___________

This exhibition is part of a broader project, which will continue through another exhibition at the Jacqueline Martins Gallery in Sao Paulo, with help from Fabio Zucker.

García Galería and Manuel Segade would like to give a special thanks to Jacqueline Martins, without whose help this exhibition would not have taken place.

sending...

sending...